The Glycemic Index In Action: More Than Meets The Eye

Integrity in scientific research and reporting is so important to me.

Diabetes is one of the leading global epidemics in Australia and around the world, and getting to the bottom of diabetes is a matter close to many people’s hearts, including mine.

As a dietitian, I’ve worked extensively in the area of diabetes management over my 10 yrs of practice so far. Now, we work on identifying insulin resistance before it gets to the stage of T2 diabetes, in the hopes of catching it early, changing habits and preventing the devastating long term ramifications of poorly controlled blood glucose levels. It’s actually a bit scary how many clients we see have “perfectly normal” fasting glucose and HbA1c levels but are still insulin resistant and en route to diabetes.

For what seems like too long now, the world of nutrition science have been in two minds about the best approach to glycemic control – high GI vs low GI, high carb vs low carb. It doesn’t help that some basic definitions like “what is considered low carb” is even inconsistent. But hey, that’s a story for another day.

Up until now, for better or for worse, we’ve still used existing evidence – both scientific and anecdotal. But this segment of the ABC Science Catalyst program has me raising my eyebrows. (full segment can be watched here).

In this video you will see that there was a before and after scan for the consumption of white bread with butter and vegemite, and another one for the consumption of grain bread with avocado. The experiment was designed to compare the rise in blood glucose levels 30min after consumption of white bread vs grain bread.

This is how it played out.

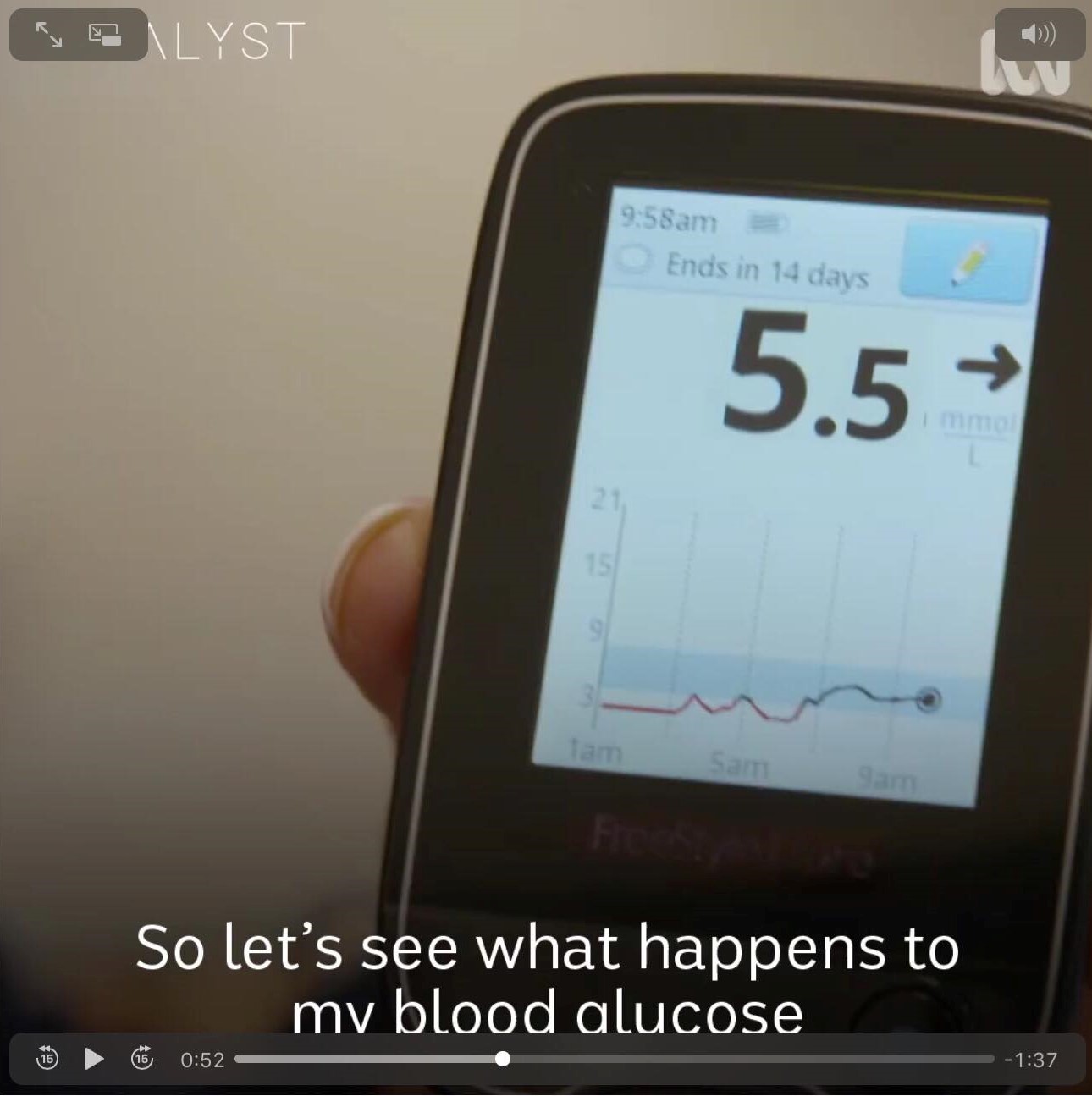

The reading for the white bread with Vegemite was taken just over an hour apart and showed a rise from 5.5mmol/L to 8.4mmol/L.

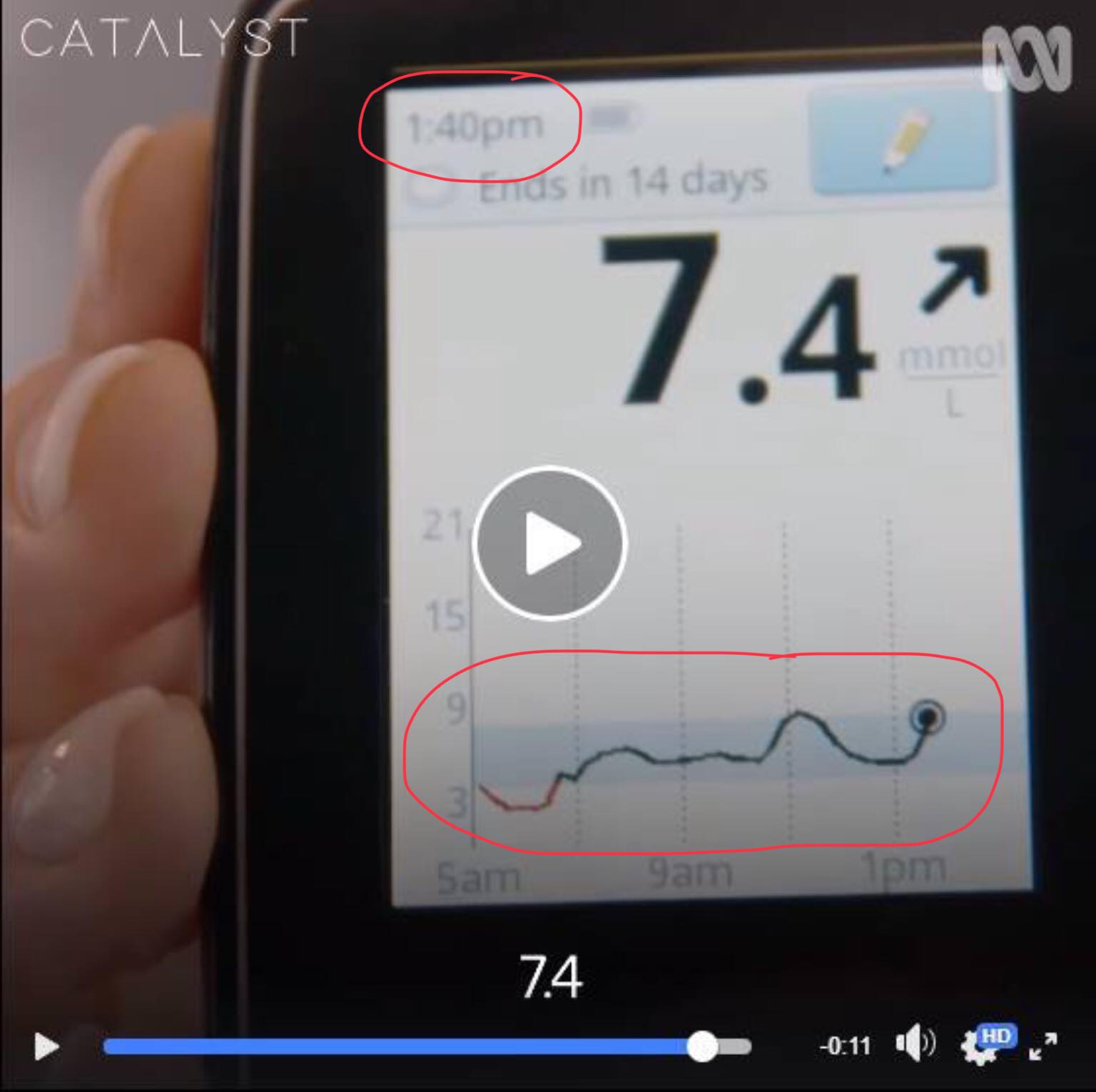

Then, the reading from the grain bread with avocado showed a before and after screen that looked identical in both the time stamp in the top left corner as well as the glucose graph on the bottom of the screen. The only change was the glucose level going from 4.8mmol/L to 7.4mmol/L. This was meant to have been taken 30min apart. (If you look closely enough at the graph on the screen showing a 4.8 reading, you will see that it doesn’t match up! The graph is clearly indicating that the glucose was closer to 9 than to 4.8!)

Ignoring the obvious, if this was an experiment designed to be credible and actually demonstrate the changes in glucose levels 30 minutes after eating white bread vs grain bread then there needs to be several changes to the way this experiment was conducted.

- The spread on top of the bread needs to be the same – c’mon, basics!

- It needs to be bang on 30min between each test – not over an hour for one and what appears to be within the same minute for the other?! (hmm…interesting)

- It needs to be taken under similar circumstances – which means at least on two separate days, at the same time each day (or at least after the same number of hours fasted since last meal)

- Other factors need to be taken into consideration, such as sleep quality, what foods were eaten before the bread, and stress levels

- When interpreting the rise in glucose, we need to look at how much it rose and not just the absolute value. For example, if looking at the absolute value, the blood glucose was 1.0mmol/L higher after white vs grain bread. However if looking at the change, in experiment 1 with the white bread, it went from 5.5 to 8.4 (a rise of 2.9mmol/L, or 52.7%). In the second experiment with the grain bread it went from 4.8 to 7.4 (a rise of 2.6mmol/L, or 54.2%). The difference is negligible. THEN, when we take into consideration that the first experiment with the Vegemite and white toast was taken 1 hour apart and the second experiment with the grain toast and avocado was only taken (allegedly) 30min apart, these two results aren’t even comparable! You cannot compare a 1hr reading to a 30min one. This demonstrates NO scientific consistency whatsoever!

- A clear definition of what glucose level is optimal / ideal. In my professional opinion, neither 8.4 or 7.4 are optimal. The one thing that I’m sure wasn’t intentional, but happened anyway, was that it demonstrated, flaws and all, that neither white nor grain bread were great – because if the glucose rose like that on a supposed “non-diabetic”, bread would be the LAST thing a diabetic should eat – white or grain.

When none of these parameters are considered and discussed, the experiment doesn’t show anything worth noting.

It’s reports like this that do NOTHING to help progress science. It only perpetuates the confusion and throws more mud on the faces of dietitians, who’ve collectively lost so much respect already for the actions of a few.

Scientific rigor is something we must all uphold, and when leading nutrition scientists aren’t leading the charge to demonstrate scientific rigor when performing an experiment or proving a point, it doesn’t speak well to the credibility of us as a profession.

This also reminds me of all that’s currently wrong with nutrition research. It’s lazy! Most nutrition research is questionnaire based, relying on subjective memory and reporting. Others are based on crude nutrient split testing on rodents, and others…are doing experiments that don’t really have consistency or objectivity behind them.

It’s research like this that has articles published one day claiming that coconut oil is the elixir to life, and the very next day, it’s become highly toxic. On moment red meat will kill us, the next it prolongs our life.

We owe it to the general population to conduct quality research and publish useful and reliable reports that actually help progress people’s understanding of health and nutrition. Instead, nutrition science has been labelled a joke!

The truth is – it all starts with the beliefs and mindset of the nutritionists and scientists themselves.

Science is ever evolving. Nutrition science is even more the case. We can believe that we are right about something, but still have it proven wrong years later.

That was how my journey went. I literally spent the first 5 years of my career recommending low fat, portion controlled nutrition to my clients. I modified everyone’s diet to include more low GI sources of carbs when their bloods indicated that they have diabetes. I didn’t remove or even decrease carbs.

It’s not to say that this is necessarily “wrong”. But 5 years ago, I realised that there was a better way for diabetics, and that was to keep carbohydrates low altogether. It made logical sense, and I went through a phase in my career where I made up a whole bunch of analogies to demonstrate the logic behind the suggestion using real life examples.

The way I’d explain low carb vs low GI to clients would be:

Imagine the M1 freeway. At certain hours of the day, the high volume of cars congests the roads. The solution the government has come up with are the traffic lights at the entrance to slow the release of cars onto the major arterial. At first it feels like it’s working. The freeway doesn’t congest so quickly. But soon, we realise that it still congests – it just takes longer.

Our blood is no different.

Carbs are like the cars in our bloodstream. Low GI carbs is like having a traffic light at the entrance of our circulation. It will slowly release into the blood – but ultimately it will still end up there.

Ultimately – the only real solution to the traffic congestion problem? Get cars off the roads.

Now, whilst that’s not entirely possible for the freeways, we can certainly do that for our blood by removing carbs. How much we remove depends on how congested it is and how congested it can get.

For me, getting to the point of overhauling my practice and beliefs around nutrition wasn’t easy. I went through a mini existential crisis – on the one hand I felt embarrassed by how much I had got it wrong. On the other hand, I was apprehensive about re-starting my career (or at least that’s how it felt!).

At that time, things could’ve gone one of two ways.

I could’ve looked at the new evidence and blocked it out, or even fabricated the outcomes of evidence in an attempt to control the conversation, just to prove to myself that my way was right.

OR, I could embrace the new information and understand that as a dietitian and a scientist, it was my responsibility to upgrade my knowledge and skillset to best serve my clients, even if it meant a knowledge overhaul.

Now, 5 years later, I’m better for it. My clients are also better for it.

Deep down I don’t doubt that dietitians all studied dietetics to become useful in solving global health issues. I don’t think any dietitian became a dietitian to do harm wilfully.

And that’s what makes me very conflicted, seeing reports like this, where a very reputable nutrition scientist is literally at the same crossroads I was at 5 years ago.

The question is, which path will she choose from here?