Category: Blog

Understanding The Ketogenic Diet – A Critique.

I have come across so many articles over the years regarding the infamous ketogenic diet. Some have been informative, some have been speculative, and some have been so riddled with misinformation that I don’t know whether to laugh at how comical it is, or cry at how misleading and dangerous it is – as dangerous as these people claim the ketogenic diet to be.

Recently, I have come across an article in the Huffington Post, discussing the ketogenic diet. It seemed to be a rather matter-of-fact article, with a prominent Australian researcher dietitian being interviewed.

What they failed to mention was that this prominent Australian researcher dietitian has vocally condemned low carb nutrition and the ketogenic diet on multiple occasions in a public forum, and is a staunch defender of the Australian Dietary Guidelines, so I wasn’t holding my breath when I read this article.

Unfortunately, as predicted, as I read on, more and more problems jumped out at me, and I couldn’t resist but put some of these bogus arguments to bed. It confuses me how someone who is supposedly one of Australia’s leading researcher dietitians can ignore #RealScience in favour of what I can only describe as “science” that #LooksLikeRealScience but isn’t.

As per my usual style, I have quoted verbatim from the original article found here, and have written my views below.

What is a Ketogenic Diet?

Clare Says: A ketogenic eating pattern is very low in carbohydrates and moderate in protein, meaning a high percentage of total energy intake comes from fat found in dairy products and meat.

A true ketogenic diet is one where carbohydrate intake is extremely low- usually less than 10 percent of your total energy intake.

I say:

A ketogenic diet is definitely characterized by a low carbohydrate, moderate protein and high fat macronutrient split.

How low the carbohydrate intake needs to be, however, varies from person to person, stage to stage of keto-adaptation, and depends heavily on hormonal status and carbohydrate tolerance. To say that a “true” ketogenic diet has less than 10% total intake from carbs is ignorant, because the automatic assumption is that anyone who is in ketosis on a higher carb split is in “fake” ketosis.

The other thing is the assumption that the fats consumed on a ketogenic diet come from dairy and meat. Sure, some do, but most people on a ketogenic diet also consume olive oil, coconut oil, avocados and nuts – none of which are “dairy” or “meat”.

How does a ketogenic diet work?

Clare says: During times of severe energy restriction (such as during fasting or starvation), prolonged intense exercise, or when carbohydrate intake is reduced to around 50 grams per day or less, the body can enter ketosis.

This means that, rather than the body burning its primary fuel source, glycogen (a complex carbohydrate, which in the human body is like petrol for a car), the body must break down fats as its main source of fuel.

If you can flip the switch and get the body to burn predominantly fat, then you produce these things called ketone bodies, which can appear on your urine and they also come out on your breath. They actually smell like acetone, like nail polish remover essentially.

I say:

A ketogenic diet aims to get people into a state of ketosis, where the body is primarily oxidizing fats for fuel. These “things” that our Prof talks about are actually by-products of fatty acid oxidation, called ketones – a water-soluble molecule that can cross the blood brain barrier to act as direct fuel for the brain when glucose is limited. Whilst you certainly can detect ketones in urine and the breath, by far the more reliable and accurate way of measuring ketones are via the blood.

Whilst it is all good and well for us to sit here and wax poetic about likening glycogen to “petrol”, the truth of the matter is, you wouldn’t use petrol in all engines. If we are to entertain our Professor and use her analogy of petrol, then we need to look at it this way – sure, glycogen is like petrol, but not all cars were made to function optimally on petrol. If you start feeding a diesel engine petrol, you are going to run into a lot of problems. This is fundamentally the problem we have today. Some people function quite well on a higher carbohydrate diet – they are metabolically flexible, quite carb tolerant, and have no issues with eating more carbs. In these cases, sure, eat more carbs. However, when you have someone who is insulin resistant, carb intolerant and don’t tend to function well with carbs (Type 2 diabetics fit perfectly into this realm, for example), the solution is not to keep feeding them copious amounts of carbs, regardless of how low the GI is. In this case, we need to promptly recognise that for these guys, their “engine” takes diesel, and we need to swap over to diesel, or we risk killing the “engine”.

Our Prof also seems to be fiercely ignorant and appear to doubt the body’s ability to “flip the switch”, but the truth of the matter is, if our Prof actually understood the #RealScience, she will know that whilst it may take some time to metabolically adapt over, fat adaptation is a sure thing that can be replicated time after time. How do I know this? Because #RealScience.

How Many Carbs Can You Eat And Still Be In Ketosis?

Clare Says: “In terms of grams, it’s somewhere between 20 and 50 grams of carbohydrates a day. To give you an idea of how much that is, one typical big slice of bread from the supermarket has about 20 grams of carbohydrate.”

In a 50 gram carbohydrate diet, you might have a piece of fruit, a slice of bread and a small potato across the day.

“That’s it in terms of foods which are good sources of carbohydrate, and the rest would come from the incidentals you’d find in milk and salad-type vegetables. It’s extremely strict,” Collins said.

“The true, original ketogenic diet can be anywhere from 80 to 90 percent fat, so they really should be considered as medical nutrition therapy. To be used at that level, you really need close monitoring.”

I say:

To be really honest – the real answer to this question is “as much carbs as it takes to still keep you in ketosis”.

For some people this may be 20g, others it may be 50g, but I also know that for some it is 90-100g.

However what we need to look at here are 2 things:

1. Total VS Net Carb

2. Carb quality

When we talk about carbohydrates, we need to look at the fibre content of these foods. Fibre is indigestible, meaning that it resists digestion, and does not ultimately contribute to overall carbohydrates that get broken down in the body. Usually when we talk about carbohydrates in the context of ketosis, we talk about “Net Carbs”, which is “Total Carbs minus Fibre”.

When the Prof gave her example of what 50g of carbs a day looked like, she mentions a piece of fruit, a slice of bread and a small potato a day.

| Food | Total carb | Fibre |

| A medium apple | 25g | 4.4g |

| A slice of bread, wholegrain | 12g | 1.9g |

| A small potato | 30g | 3.7g |

| TOTAL | 67g | 10g |

| Net carb |

57g |

|

When you look at that, you think “omg that’s NOTHING! If I eat ANY veg, it will blow my daily limit way over!”

But the truth is, no one who is actually serious about keto would ever opt for any of those foods to be part of their diet. Instead, they would choose nutrient dense, fibre-rich foods, as this not only ensures nutritional adequacy, it also means they get to eat a LOT of food.

Now let’s take a look at how it is actually done:

| Food | Total carb | Fibre |

| Green beans 100g | 7g | 3.4g |

| Zucchini 1 medium | 6g | 2g |

| Broccoli, 1 cup | 6g | 2.4g |

| Spinach, 100g | 3.6g | 2.2g |

| Silverbeet 100g | 3.7g | 1.6g |

| Avocado 1 whole | 17g | 13g |

| Raspberries 1 cup | 15g | 8g |

| TOTAL | 58g | 32.6 |

| Net Carb | 25.4g | |

What you can see here is that even after close to 1kg of vegetables and berries, your net carb is ONLY 50% of the “50g” our Prof keeps talking about. Being a DAA spokesperson, our Prof’s stance on nutrition is “plant based is best” – well, not going to lie, 2 kilos of “plant based foods” a day is pretty darn plant based to me!

Furthermore, what nutrients do a piece of fruit, a slice of bread and a small potato offer that 2 kilos of different vegetables and fruits don’t offer?

Absolutely NIL.

Even if we were to lower carbs for those who need to consume less to achieve ketosis, the above example illustrates that with a combined 1kg of vegetables and some fruits, this is still achievable, without compromising variety or quantity of food.

So, remind me again how a ketogenic way of eating is all “meats and dairy” and “restrictive” again?

C’mon Prof – I find it worrying that a professor in dietetics would attempt to wilfully mislead the general public into believing that low-carb is restrictive and meat-based. However, if it isn’t wilful misleading, it concerns me more that a professor in dietetics doesn’t already know this information. Either way. I am concerned.

How Do You Know If You Are In Ketosis?

Clare says: While it depends on “many individual variability”, the time it takes to burn fat and produce ketone bodies is typically about three days of carbohydrate restriction, or three days of severe total food restriction, Collins explained.

“The way you find out if you’re ketogenic (if you’re producing ketones) is you buy keto test strips at the chemist and you test your urine.”

I say:

Yes, there is a lot of individual variability – like hormone levels, metabolic health, current dietary intake, et cetera that can affect how quickly or slowly someone gets into ketosis. However “blowing” (as per previous reference of nail-polish breath) or “peeing” ketones is not exactly the same as burning fat for fuel as is evident in those who are properly keto fat-adapted.

Let me explain.

Ketones are by-products of fatty acid oxidation. Our bodies produce ketones routinely when the liver breaks down fat. However, the production of ketones alone is not suggestive that the body has switched over to using fat as its primary fuel. When we talk about the physical, mental and metabolic benefits of ketosis, we are actually talking about the benefits as seen in those who are properly fat-adapted. This is something that can often take weeks to months to properly achieve.

So, quite apart from the fact that the Prof assumed that “producing ketones” equated to being “ketogenic”, she also made the grave mistake of assuming all forms of testing are equally reflective of being ketogenic, and finally makes a fly-away comment about how buying keto test strips to check urine ketones will suffice in concluding whether or not someone is in ketosis.

If the Prof looked into the #RealScience further she would have realised that there are in fact 3 different ketones – acetone, acetoacetate and beta-hydroxybutyrate. Of these 3 ketones, acetone is what is detected in the breath, and is a ketone that results from breaking down acetoacetate. Acetoacetate is usually detected in the urine, and is excreted in this method when there are excessive ketones in the body.

When you test urine, blood and breath ketones you will see that there is very minimal correlation between rising or falling blood ketones, and that of urine and breath ketones. Further to this, urine ketone levels decrease as someone becomes more and more fat adapted, as their body will become more efficient at using ketones, instead of just peeing it out.

Because of these subtleties, we believe that blood ketone readings to assess the level of beta-hydroxybutyrate is typically the best way to assess ketosis. As per Phinney and Volek, nutritional ketosis is achieved when blood ketones are consistently sitting between 0.5-3.0mM. Whilst ketones can be safely higher, it isn’t always better or even necessary.

The Pros of a Ketogenic Diet

1. Effective short-term weight loss

Clare says: According to the Dietitians’ Association of Australia (DAA), following a ketogenic diet will “undoubtedly result in short-term weight loss” which probably comes down to a few factors:

• A reduction in total kilojoule intake

• The depletion of liver and muscle glycogen stores and associated water

• A reduced appetite(which is a side-effect of metabolising ketones, and also due to satiety associated with eating foods containing fat and protein)

I say:

Not going to lie – the DAA is not a very reliable place to be quoting anything on the topic of low-carb or ketogenic nutrition, considering the DAA still believes that saturated fats cause heart disease, and low carb diets are fads. When you jump onto the DAA website and browse through their list of Hot Topics, you can see just how mislead they still are when they desperately try to stamp authority on topics that they frankly have no authority over. The most comical part is how they are constantly trying to convince the general public to see an APD (which I am one, by the way) on topics that they show no leadership, understanding or even openness towards – yet, apparently, they are still the go-to experts? Frankly I am a bit embarrassed by that, especially when their go-to alternative is the Australian Dietary Guidelines, which still to this day believe that saturated fats are found in commercial biscuits and cakes.

My point is further substantiated in the fact that the DAA believes that a ketogenic diet works because of a “kilojoule reduction”. Last time I checked, the entire premise behind the ketogenic diet was a change in macronutrient ratio – not a kilojoule deficit. In fact, in most cases, if one was to simply swap out their carbs for fats, gram for gram, they will in actual fact end up with more kilojoules. At no point is it suggested or even recommended that this way of eating needs to be (or even should be) a kilojoule reduction.

Also – for everyone who has ever tried to cut calories when eating a “portion controlled” diet, the number one complaint is that they are always hungry. So, again, not going to lie, if someone was able to feel more satisfied, eat plenty of food, and lose weight, I hardly see that as a negative thing that our Prof makes it out to sound.

2. May help to manage epilepsy in children

Clare says: if you have a child whose seizures are so severe and frequent, no medications are working, have frequent accidents and need to wear helmets to protect their heads, then of course you would try it. This is why it’s quite annoying how flippantly the ketogenic diet is being discussed as “hey, yeah, let’s go keto”.

I say:

Hold. Up.

So, what I am hearing you say here, Prof, is that there is a diet made up completely of natural, real, whole foods that can fix a debilitating condition and return to someone their quality of life that no medication with a staggering list of side effects can achieve; yet – you don’t see the wonder in how food has effectively trumped medicine in this circumstance, and instead of then realising how this natural and non-invasive way of eating should be the first line approach, you taunt at it like it is a crappy last-resort?

Can we not see the irony in all this?

Also – if currently dietary protocols are so effective at improving the health of the population, why would so many people so “flippantly” decide to try a ketogenic diet and realise through the process that all their joint pain has gone, their brain fog has disappeared, they no longer think about food all day long, their energy levels are better, their mood is better and the weight that has been accumulating around their midsection has now successfully come off, allowing them to realise that they aren’t just getting older – but they were in fact getting sicker, something a change in diet and metabolic pathway via the ketogenic approach has helped them fix.

Something that if only you would read more into, instead of just applying your hard-wired confirmation bias against, you would realize is grounded in #RealScience, unlike the ADGs which you blindly push, which at best only #LooksLikeRealScience.

3. May have positive effects in the treatment of some cancers

Clare says: “I will preface this with: do not try this at home,” Collins said.

“There is research, predominantly in animals studies, looking at the use of the ketogenic diet for optimising outcomes during cancer treatments. This is absolutely medical nutrition therapy at its highest level. If you throw yourself willy-nilly onto a ketogenic diet during cancer treatment, you risk becoming malnourished.

I say:

Look – I won’t disagree in that the effect of a ketogenic diet on cancer is currently not well established, and that a ketogenic approach is definitely considered medical nutrition therapy in the context of cancer treatment. However, I do not believe that following a ketogenic diet during cancer treatment will lead to you being malnourished. The only reason anyone would think that is because they fundamentally think that the ketogenic diet is malnourishing, which is simply not true.

The cons of the Ketogenic Diet

1. It can lack phytonutrients, fibre and B-vitamins

Clare says: Due to the carbs found in many fruits, vegetables, whole grain and legumes, these healthy, high-fibre foods are extremely limited, which can lead to issues such as constipation and nutrient deficiencies.

“What concerns me about the people who are absolute purists on the ketogenic diet, is it means you’re cutting out groups of food which offer a lot of protection — namely vegetables providing phytonutrients and fibre which help with bowel cancer and managing body weight,” Collins said.

I say:

The truth is, there are extremists in all different styles of eating, and extremism is not what we promote, no matter what it is in the context of.

Even “healthy eating” at the most extreme has been dubbed “orthorexia” and is not encouraged.

However, when we talk about the ketogenic diet, it is important we look at it in a very objective way, based on it being a macronutrient manipulation to assist those, who would benefit, enter into a state of nutritional ketosis. When we look at what a typical person would do on a well-formulated ketogenic diet, plant-based foods like vegetables, avocados, nuts and plant oils such as coconut oil and olive oil are encouraged and consumed in abundance. Well sourced, quality meats, fish, poultry and eggs are also encouraged, as are some dairy products such as cheese.

When you look at the ketogenic diet objectively, you will realise that it is a diet rich in phytonutrients, fibre (as we have sufficiently demonstrated in my earlier example) and B-group vitamins. In fact, I cannot think of a single nutrient that “wholegrains”, breads, pastas and high-sugar fruits offer that cannot be met on a ketogenic diet, and I hereby challenge the Prof to come up with one herself.

2. Can affect gut health

Clare says: As well as helping to fill us up, fibre is vital for a healthy gut, such as supporting the growth of ‘good’ bacteria and keeping the bowel lining healthy. With Australians on average already not meeting the recommended daily amounts (25g of fibre for women and 30g for men), a ketogenic diet will make it harder to meet these targets.

“Long term, coming back to a dietary pattern which allows them to eat whole grains, lots of vegetables and fruit is what’s best for their overall health and wellbeing,” Collins said.

I say:

Firstly I need to point out (again!) that a ketogenic diet is not void in fibre. Based on our earlier calculations, if you were to go by “50g of total carbohydrate” you will still be able to consume 30g of fibre, which according to our Prof, is meeting the fibre needs of both men and women. Furthermore, this works out to be less than 25g of net carb a day – so, if you were to double the carbs to make up 50g net carb, you will be consuming TWICE the amount of fibre that our Prof deems necessary for “gut health”.

However, as we understand the gut better, we know that the indigestible fibres feed the gut by fermenting in the large intestine to short chain fatty acids. Funnily enough, butter and cheese are two of the richest dietary sources of butyric acid, a short chain fatty acid.

So, the only way I see that a ketogenic diet affects gut health is in a positive way, providing ample sources of short chain fatty acids to fuel healthy gut microbiota.

3. It’s not sustainable

Clare says: One thing the ketogenic diet ignores is that not all individuals will benefit from, or even require, the diet — nor is it sustainable for the long term.

As the DAA explained: “The key to maintaining a healthy weight in the long-term is an eating pattern that is sustainable over time. With this in mind, dietary recommendations should always be tailored to an individual — as everyone is unique, and what works for one person, may not work for another.”

“You’re not going to have much joy eating on a ketogenic diet. You’re going to have sticks of celery with cream cheese for snacks and bacon and eggs for breakfast, but there won’t be any warm toast or flavours from a range of vegetables, fruits and legumes,” Collins added.

Other short-term side effects of ketosis can include fatigue, bad breath, nausea and headache.

I say:

Lucky for the general public, the DAA is not the one doing a ketogenic diet – therefore it is completely not up to them or the Prof to decide what is, and what isn’t sustainable long term for each individual of the public.

The worst part of this entire statement is the Prof’s petty attempt to convince the reader that breads, fruits and legumes are more palatable and inviting than bacon, eggs and cream cheese. Worst still, she throws in some short term side effects to completely deter someone from thinking keto is a good idea – I mean, nobody wants short term nail-polish breath…right?

Conclusion

The part that riles me up the most really is the fact that The Huffington Post decided to write a feature on the ketogenic diet – however the tone was set from the get-go that this was one not in favour of the ketogenic diet. Not only did they use all journalistic attempts to make keto sound like the worse-off cousin to the ADGs, they also interviewed the Prof, one of the most well known anti-low carb dietitians the country has seen.

There are so many experts who would have done a much better job; so many individuals who have such inspiring stories of their own health journey with keto to share – yet, a dietitian that more or less calls the ketogenic diet an unsustainable, nutrient poor fad was the one chosen to talk about a topic she has no personal experience with, and by the looks, no #RealScience knowledge on.

A MONTH WITHOUT SUGAR – A Critique.

This is the thing. As a dietitian, it is 100% our jobs to help guide clients through all the science and junk science around nutrition. It is our jobs to critically assess all dietary protocols so we can ascertain which ones are scientifically sound, and which ones are not, so we can then make suitable and responsible recommendations to our clients.

Our jobs are to educate, to inspire and to promote good health, and healthy habits.

Yes, we get lots of clients who complain about “how difficult it is to” do something, like cut out sugar, or grains, or dairy, or gluten – and whilst not all people NEED to cut these foods out, some do, and for those that need to, we need to be there to support them, not give them a way out of achieving optimal health.

Unfortunately, this dietitian chose to ignore sound science in an attempt to bro-down with complainers and rather than take on the role of educating and inspiring, she did exactly the opposite.

Here, I assess what her experiences were, bit by bit, quoting her verbatim, then providing a running commentary of my thoughts at every turn. Perhaps these views are just that of my own, perhaps they are shared by many who have read her article – but alas, here is what went through my head.

Day 1: While eating whole-wheat crackers with my super-healthy salad (feeling great about my food choices), I check out the crackers’ ingredients label. WTF? Cane sugar! Day 1=fail.

Eating whole-wheat crackers, this dietitian realised, mid-bite, that her cracker has cane sugar in it.

WTF – was her reaction.

WTF – was my reaction to her reaction.

Label reading is a valuable tool we teach to our clients, to help them identify nutritional composition and nutrient value and quality from looking at the ingredients. Since her entire goal over the 30 days was to cut out added sugar, I would have assumed that her first step would be to ensure that her food for those 30 days fit the criteria?

The other part of this that confused me was the need to include crackers with an otherwise “super healthy salad”? I don’t even know what “super-healthy” is supposed to mean – to me that means a salad that has an abundant amount of healthy fats and quality proteins – which, if you were to consume, you will realise that the crackers become quite redundant, both from a satiety perspective and from a nutrition perspective (crackers are REALLY NOT that nutritive!).

Day 2: My oatmeal definitely tastes a little bland without a scoop of brown sugar, so I head to the store and pick up some naturally sweet foods, such as dates, bananas, red grapes, and papaya. Problem solved.

Or so I thought… until lunchtime, when I add Sriracha to my rainbow grain bowl. Surprise—Sriracha has sugar. I guess I need to read EVERY single food label.

See, the problem I have with this is the fact that she genuinely believes that replacing brown sugar with a piece of fruit is the real answer to this problem. She completely fails to address the fact that her meal has a disproportionate amount of total carbohydrates and sugars to any of the other nutrients (pretty much zero protein or fats), and rather than using her 30 day challenge as a way to see how she could improve her diet, she uses this as a way to completely take the piss. She replaces one source of sugar with another. Whether she is deliberately misleading and misguiding her readers or not, I don’t know – but if she was out to actually educate, she will admit that adding brown sugar or fruits is not helping her increase her total protein in that meal, which is a key nutrient to help stabilise blood glucose levels and improve satiety. Sure, she didn’t need to swap the oats out for bacon and eggs (although I would, and I don’t know any of my clients who wouldn’t!) but she could have at LEAST tried to replace her brown sugar with nuts, seeds and add some natural full fat Greek yoghurt, no?

And then at lunch – again I have no idea if she is taking the piss (which is irresponsible in any case) or she is serious, but adding a sugary sauce to a high-carb meal which is extraordinarily void of proteins and fats AGAIN???

So hang on a sec – her usual diet would have consisted of this so far:

Breakfast – oatmeal with brown sugar

Lunch – rainbow grain salad with sriracha

So, let me ask: where exactly is the protein or the fats in this day?

Why are we not adding some chicken or some tuna to that salad with some avocado and olive oil (or, even better, some Primal Kitchen Mayonnaise)?

And again on the label reading – if you’re going to essentially eat all packaged foods, then it is a good idea to read your labels. The alternative is to opt for fresh produce without food labels.

Day 5: I’m getting the hang of this no-sugar thing, but I have a dilemma. Today I’m running the Brooklyn Half. Since this is my 10th half-marathon, I have a pretty standard fueling routine that consists of water for the first six to seven miles, followed by a sports drink for the second half of the race and a CLIF Shot Blok around mile eight or nine. In other words, my usual fueling plan is loaded with sugar because sugar (a.k.a. glucose) powers muscles during endurance activity. Luckily, another dietitian (and marathoner) told me to try dates, stuffed with peanut butter and sprinkled with sea salt, for the right mix of sugar and sodium. Although I don’t like to try anything new on race day, I make an exception and opt for the dates instead of the Shot Bloks. They worked pretty well. The only problem was I got an annoying cramp around mile seven that wouldn’t go away, so I gave in and reached for a sports drink.

Look, this is the thing. When you have fuelled performance on glucose all your life and you are eating an exorbitant amount of carbs a day, sure, you will 100% struggle changing that up so close to a big race. However, there is something called fat-adaptation, where you can train your body to use fats as the primary fuel for endurance performance. Many marathon runners, triathletes and road cylists that I have worked with over the years have reported a significant improvement in performance, recovery and the lack of needing to constantly fuel during a race. This however is not an overnight feat. Usually we spend a few months helping them fat-adapt, but once they are adapted, they become unstoppable.

However, as a dietitian, we need to understand that there is more than one way to do anything, and for those who are metabolically flexible, fuelling with more carbs is 100% a way to go. However, for those who tend to struggle with central adiposity, insulin resistance or diabetes, fat-adaptation may just be the key for you.

Day 7: All in all, I feel like the first week was much harder than I anticipated. #fail. Between the added sugar in my crackers and Sriracha and my sports drink during the half-marathon, I’m beginning to understand how incredibly difficult it is to omit an entire ingredient from your diet.

No, just no. cutting out added sugars is really not that hard. There are a myriad of options and suitable ingredients to replace sugar with. And another thing – sugar isn’t just an ingredient. It is literally considered universally as a discretionary ingredient that we should be limiting or eliminating. However, when we have dietitians tossing in the towel to cutting out sugar, we can only imagine how many clients she will be inspiring to do the same, even if for them it is actually a valuable change to improve their overall health outcome. There is no morale or chance amongst the soldiers if the general has already succumbed to failure.

Day 12: I started this journey midweek, so day 12 is the beginning of my second weekend. Since I cook most of my meals during the week, I’m able to control what goes into my food. But on the weekends I enjoy an occasional brunch or dinner out.

Do you know how annoying it is to ask a waiter if there is any sugar in the food? They look at you like you are the worst person ever. Needless to say, I’m not able to tell if there is added sugar in some of the foods I don’t prepare myself, but I do try to stick to the foods I expect have less.

Do you also know how annoying it is to ask a waiter if there is gluten or nuts or egg if you had an allergy to any of those things? Sure, she isn’t allergic to sugar, but the sentiment is the same! And the answer is – it isn’t annoying at all!

When I am out, I ask for modifications all the time!

“Can I please get an extra egg with that, and no toast, please?”

We are usually met with a “yeah, sure!” and a massive smile. (Certainly not a look like I am the worst person ever….maybe she needs to find a new café!)

Cafes are so used to this now, they barely bat an eyelid. The reason this dietitian gets uncomfortable is because of her own fear – fear of being judged, fear of being ridiculed. But let me ask – could that be because she is judging and ridiculing those who are asking for these modifications at cafes? Probably so.

Day 15: Halfway there, and it’s finally starting to feel easier. I’ve become accustomed to sweetening my morning oatmeal with bananas and eating pre-workout snacks with natural sugar (dates and peanut butter, anyone?). I can definitely do this for two more weeks.

Good to hear…I guess? Although if I am to be completely honest, I don’t know how it feels easier- I mean, there has been no real reduction in total sugar intake, nor any improvement in protein or fat consumption – so honestly, I don’t know if the “easier” is a mental one (because she’s half way through her challenge of doom) more than it is a physical one, because I can’t see how she could actually be experiencing any metabolic improvements with her choices of “added sugar” replacements.

If she had actually replaced her added sugars with proteins and fats, she would likely, by this point, have an increased sense of fullness, meaning she won’t need snacks between meals, and improved mental clarity. This would have come about from not having such high glucose and insulin spikes and subsequent low dips throughout the day, keeping her energy levels, hunger levels and mental focus more consistent throughout the day.

If she had needed to lose any weight, she would have started to really notice it by this point too – not because of a reduction in calories, but by a reduction in insulin secretion.

Day 16: Googles, “Does wine have added sugar in it?”

Can’t find a definitive answer.

Pours glass of wine.

Her Google: “Can’t find a definitive answer”

My Google: “100ml of wine has 0.6-0.8g of sugars depending on whether it is red or white”.

I think I like my Google better.

Day 17: Status quo. Omitting added sugar from my diet has made my already healthy diet even healthier. I have no choice but to eat plenty of fresh fruits, veggies, and whole grains. But tomorrow I’m traveling to California for vacation. My boyfriend looks at me and says, “You aren’t going to do this on our trip, are you?” I think he doesn’t want to listen to me complain.

Ok well it really depends on your perspective of what a healthy diet is and what you consider “healthier”.

Sure, if you are replacing added sugars with fruits, then yes, nutrient wise, it is 100% denser. But if you are looking at it from a is-this-going-to-help-her-sick-clients-feel-better sort of way, the answer is “no”. The problem here is not “which source of sugar is better” it is the fact that we need to start assessing the diet for whether or not it is nutritionally complete! Does this diet include adequate amounts of quality protein and fats? Does the diet have a rich and varied amount of vegetables?

And not going to lie – if I was on a journey to improve my health, and my partner looks at me and essentially says “stop being healthy so I can feel good about eating crap with you overseas” I would not be with my partner today.

Instead, partners are meant to be supportive and understanding – my partner has Crohn’s disease, and after we changed his dietary protocol to reduce inflammation and heal his gut, he (after 17 years of being on fortnightly injections of Humira, and after 2 bowel resections) is now, for the last 12 months and counting, medication and inflammation free. Never once did I give him shit for not having a glass of wine with me, or not eating grains, or sugar. When he over did the cheese and got a mild flare, he subsequently cut dairy out and not once have I complained to him about doing that. His nutritional markers are all perfect. His bone density is perfect. His health is perfect. And the unexpected side effect? He’s lost 22kg and has amazing energy levels and mental clarity.

So the moral of this story? Support your partner, and FFS, support your patients! They don’t come to you for you to tell them how impossible it is to do something – what they want is for you to encourage them and always have their overall long term health as your best interest.

Day 23: All self-control goes out the window when I’m tired. We arrived in California last night, and I’m super jet-lagged. I need an afternoon cookie to make me feel better. And let me tell you… it worked.

Hate to break it to you guys – it’s not self control – it is hormonal. After a long flight, your body is under more stress than usual. Funnily enough it is the cortisol spike that has you wanting sugar – not a lack of self control ?

A much wiser choice would be some cheese or salted macadamias that can help provide energy without the sugar spike.

And instead of a coffee, water at this point would have been a much wiser choice for hydration – but hey, we all love a good coffee!

Conclusion

1- This confirmed my right to roll my eyes at diets that eliminate entire food groups, because it’s nearly impossible to sustain that change for the long term. I’m a dietitian, and I wasn’t able to do it for longer than a week without a slipup. And the problem with slipups is they breed feelings of discouragement and kill your motivation to continue.

First – sugar is NOT a food group.

Being a dietitian doesn’t make you more intelligent, and clearly, not more resilient. However, cutting sugar properly would have stimulated a metabolic shift, which would have made keeping it up long term a walk in the park. The key is not to never have anything with sugar in it (added or natural), but it is about understanding fully the role sugar plays in disease and inflammation and being able to make the right recommendations around it.

2- To completely understand what you are eating, you must really dig into food labels. Sugar has many aliases, and it hides in foods you wouldn’t normally consider, such as tomato sauce, barbecue sauce, pickled veggies, and multigrain crackers. Look for ingredients such as high-fructose corn syrup, molasses, dextrose, glucose, malt syrup, corn syrup, or caramel on the label, and run from them if you’re avoiding added sugar.

Sure- and that is our jobs as dietitians to not only highlight this point, but educate on it, so our clients can walk away confident they know what they are looking for.

This really shouldn’t be a deal breaker.

3- It’s nearly impossible to know what’s in food you don’t cook, so be aware when you’re going out to eat. And good luck asking your waiter if they use sugar in their marinara sauce.

Here’s an idea – keep your choices as low in added sugars and total carb as possible, eat at home as often as possible – but otherwise, enjoy yourself when you are out for a meal! Life long healthy changes are not made or broken in a single meal out, but rather in our mindset, and our long term choices and behaviours.

4- Cutting out one food group made me crave it more. By the end of the 30 (or, well, 26) days, I was dying to eat a piece of chocolate (or a cone filled with coffee).

Again – sugar is NOT a food group and cutting it out was not making you crave it more lol – the truth is she really didn’t cut it out at all! Sure, no “added” sugar, but when your diet is mostly carbs and natural sugars, once it breaks down in your blood stream, physiologically, your body is not going to go “hmmm, this glucose came from a rainbow grain bowl…let’s metabolise this differently to that glucose she accidentally consumed from the sriracha”.

If she had actually reduced total carb (and limited to just a small amount of fruit and starchy veg), and subsequently increased her protein (which her protein count was next to ZERO before dinner time) and her healthy fats, her experiences with cravings would have played out much different to the way they did.

5- Rather than making incredibly difficult changes to your diet, it’s much easier to make small changes, like adding more fruits and veggies to what you already eat. A bunch of small changes add up to one big change over time.

If I had a client sitting in front of me with 19.2mmol/L fasting blood glucose – I would not be making any small changes – because by the time we made all these small changes, my patient would have ended up with no legs and on dialysis. Patient care will always be my number one, and part of that includes recommending what works, and what is right – not just what is “easy”. The other part is encouraging them, instead of deflating their hopes by smacking them over the head with your own failed attempt at something otherwise so simple.

Mindfulness and Weight Management

This month, our fabulous Metro Dietetics team has presented a range of high quality and evidence-based articles around weight management. Today, I am going to showcase some simple strategies that I like to refer to as the missing puzzle pieces of weight management.

I am not going to lie, these will not guarantee you fast or extreme weight loss results in a short period of time. However, these strategies will help to form the basis of healthy lifestyle modification, which goes hand in hand with modifying the types of foods eaten. Furthermore, these strategies will help to ensure slow and steady behavioural changes, which off-set the vicious effects of yo-yo dieting and weight-cycling. The notion is around MINDFULNESS, which I think is fitting given the cult-like behaviours we are seeing more often around our food choices.

Okay, I’m going to cut to the chase. Please read on if you’re with me.

At this point in time, I am focusing on HOW you’re eating rather than WHAT you’re eating.

Eat slowly, chew well

Have you ever considered the pace at which you eat? This is a big one yet it’s not something we consciously think about. More research is demonstrating that the pace at which we eat can influence the quantity of food we ingest at meal times.

In general, those who eat quickly tend to eat more than their counterparts who eat slowly. It takes roughly 10-15 minutes for our gut to signal to our brain that it is feeling full. Therefore, a person who eats slower is better equipped at recognising their body’s ‘fullness’ signal because they have allowed sufficient time for this response to occur, hence are more likely to stop eating before they overeat. In contrast, those who eat quickly are more likely to have already finished their entire dinner plate before feeling overly full.

Take home message and useful tips:

> Slow down the pace of your eating by chewing your food well

> Swallow your food before starting your next mouthful

> Using smaller cutlery can help you to take smaller mouthfuls

> Place your cutlery on the table after each mouthful

This is not something that can be changed over night – you may need to retrain your brain which could take a number of days or even weeks.

Food psychology is important

Many of us have been programmed since children to finish our plate. As a result, we tend to mindlessly fill up our dinner plate to the brim, then feel the need to gobble up every last mouthful.

One tip I encourage is to reduce the size of your dinner plate, if you’ve identified that this is an issue for you. The psychology behind this is that you’re still creating an illusion that your plate is full, which is in fact correct. However, it’s a smaller amount to what you would have typically served up, prompting you to eat less but still be satisfied with that amount. The key is not to make the PILE of food higher. Remember, there will always be more food to go back to if you are still feeling hungry.

The Great Divide

If you’re still feeling unsure about the amount of food to add to your dinner plate, then this might be the strategy for you: dividing your plate up. This strategy is being adopted more often today, and I think it’s a great one.

Here’s how:

1- Fill up your dinner plate and then divide it in half.

2- Eat one half of your dinner plate.

3- Pause for 10-15 minutes. Remember, you must allow time for your brain to register its level of ‘fullness’. Reassess your hunger levels.

4- If you’ve identified that you’re not quite satisfied, divide your plate in half again, so that you are left with two original-sized quarters.

5- Eat one quarter. Pause for 10-15 minutes.

6- Attempt to stop eating at this point if you feel satisfied after your pause. If not, you are entitled to finish the remainder of your plate.

This will not only help you to slow down the pace of your eating, but will also enable you to become more intuitive with your eating. A dietitian with a special interest in this approach will be able to provide you more guidance around this strategy.

Minimise distractions at meal times

This point goes hand in hand with Point 1. One reason we are likely to overeat at meal times is due distractions including TVs and phones. How much attention are we really paying to what we’re eating, how we’re eating and how much of it we’re eating? The answer is most likely: very little. I challenge you to trial a TV-free or phone-free meal time, at least three times a week. Instead, focus on the actual activity of eating. Pay closer attention to your food. What does it look like, what does it taste like? Was it saltier than you imagined? Perhaps crunchier than you imagined? How quickly are you eating? Do you need to slow down? Familiarise yourself with the food you’re eating, regardless of whether you cooked it or not. You may discover things you’ve never noticed before. Perhaps you may have never appreciated the time and effort that goes into cooking if you do not routinely cook the food yourself.

Conclusion

These topics are only the tip of the iceberg when it comes to exploring mindful approaches to healthy eating and weight management. While they may not be applicable to everyone, they certainly make up the fundamentals of our eating habits, but are ironically and consistently overlooked as important aspects of our eating.

If you would like specialised advice around mindful eating, make an appointment to see one of our nutrition experts!

References:

Angelopoulos T, Kokkinos A, Liaskos C, et al. The effect of slow spaced eating on hunger and satiety in overweight and obese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care 2014;2:e000013. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2013- 000013

Kausman, R. (2004). If Not Dieting, Then What? New South Wales, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Wilkinson L, Ferriday D, Bosworth ML, Godinot N, Martin N, Rogers PJ, et al. (2016) Keeping Pace with Your Eating: Visual Feedback Affects Eating Rate in Humans. PLoS ONE 11(2): e0147603. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147603

Willer, F. (2013). The Non-Diet Approach Guidebook for Dietitians. First Edition. United States: Lulu Publishing Ltd.

Healthy Eating Doesn’t Have to be Expensive

When it comes to implementing lifestyle changes one of the most common barriers is money! It is true that big food companies are taking advantage of health triggering words like “fresh” and “organic” as a means of ramping up prices. It is therefore important that we consumers are aware of such marketing techniques and learn to choose foods that will help our bodies function optimally and protect against disease, irrespective of whatever health claims may or may not appear on the packaging. So when it comes to making these choices, consider the examples below and learn how you can increase the nutritional content of your favourite meals and snacks while saving some hard-earned cash at the same time!

Nut Bars vs. Mixed Nuts

| ✓ Unsalted Mixed Nuts | $15.70/kg | Nut Bar | $25.00/kg |

A good quality nut bar is at very best, 75% nut (well if you are being technical it is far less than this because the majority of nuts comprising these bars are peanuts – which is actually a legume!). So what makes up the remaining +25% of these crunchy snacks? You guessed it – sugar! The subsequent 3 ingredients are literally sugar, sugar and sugar (precisely “invert sugar, glucose, honey”). So don’t be fooled by these expensive treats, there is a much cheaper and healthier way to do it. For less than two thirds of the price, you can stock up on a packet of unsalted mixed nuts which can be easily portioned into 30g zip lock bags and taken with you wherever you go! Eating just a handful of nuts a day can reduce the risk of developing heart disease by 30-50% (1-5). Even people who only eat nuts once a week have less heart disease than those who never eat nuts (4). In addition to these heart-protective properties, nuts also have a GI-lowering effect (6-8) which means that they help to stabilise blood sugars if consumed with carbohydrate. This is likely due to their contribution of fats and fibres which both slow digestion and thus, the release of glucose into the bloodstream. So whether you eat them on their own as a snack or throw them into your natural yoghurt or smoothie, nuts are worth every cent when it comes to your health!

Potato vs. Pumpkin

| ✓ Pumpkin | $1.50/kg | Potato | $4.00/kg |

Potato is a staple in many Australian homes and has been for many years. However, our population has also become increasingly insulin resistant as evidenced by the undeniable prevalence of large waistlines and epidemic rates of Type 2 diabetes. Insulin resistance manifests after a chronic period of eating more carbohydrates than one’s body can handle. The pancreas ramps up insulin production to deal with or prevent abnormally high levels of blood glucose. Each person’s carbohydrate tolerance is different and you may well be insulin resistant despite producing “normal” levels of blood sugar. An easy non-invasive measure of insulin resistance is waist circumference, with Australian targets being < 94cm for men and < 80cm for women. This is because visceral fat (stored around our internal organs) has an extremely strong positive association with insulin resistance (9). So what does all this have to do with the humble potato, and why is pumpkin a healthier (and cheaper) choice? Well, 100g of potato contains 18g of carbohydrate while the same amount of pumpkin contains just 6g (10). At any one time a (non-diabetic) person has around 1 teaspoon (5g) of sugar in their blood (11). With the knowledge that carbohydrate breaks down to glucose in the blood, it is easy to see how potato will produce a much greater rise in blood sugar and ultimately require a much greater amount of insulin to deal with such! If you have insulin resistance then your pancreas has to work even harder to clear glucose from your blood, so it seems only sensible to choose foods that are lower in carbohydrate where possible. Pumpkin is also abundant in many essential micronutrients such as the antioxidants vitamin A, C and E. You can make the most of it by keeping the skin on, for extra fibre, and by roasting the seeds to sprinkle over your meal, for healthy monounsaturated fats, protein, iron and zinc. Pumpkin can be roasted, stir fried, mashed or pureed – just like you would use potato.

Packaged Crumbing Mixtures vs Desiccated Coconut

| ✓ Desiccated Coconut | $8.00/kg | Pre-made Crumbing | $11.70/kg |

Everyone loves a good crumbing, whether it be on your chicken, fish or even on the top of your cheesy veggie bakes! Well it’s time to clear the pantry of nutrient-void bread (or Corn Flake) crumbs and say hello to desiccated coconut. Pre-made crumbing mixes tend to be full of unwanted additives such as sugar, salt, artificial flavours and preservatives. Desiccated coconut on the other hand is literally just that – coconut! Coconut meat is high in medium chain triglycerides which are preferentially converted into fuel for the body to use for energy, with little chance of being stored as body fat. Coconut also contains fat-soluble vitamins A and E, alongside polyphenols and phytosterols (12). These properties of coconut meat may be a reason the Kitavans of Papua New Guinea or the Tokelaus of New Zealand, whose staple food is coconut, have no incidence whatsoever of stroke and heart disease in their respective populations (12). Not only is it good for your health and waistline, but desiccated coconut is a perfect alternative for those who many have allergies or intolerances to wheat, gluten or chemicals that tend to be hidden in these types of foods (and don’t forget, it’s cheaper!). Coconut forms a rich, crunchy coating and can be used just like any other crumbing mixture. It even adds depth with it’s unique nutty flavour and you might even like to season it by tossing through your favourite herbs and spices!

Frozen Yoghurt vs. Natural Yoghurt

| ✓ Natural Yoghurt | $5.00/kg | Frozen Yoghurt | $14.30/kg |

There is a huge misconception that frozen yoghurt is somehow a healthy option, likely due to the inclusion of the word “yoghurt”. Not only is frozen yoghurt almost three times the price of natural yoghurt, it also contains quadruple the number of ingredients (17 vs. 4)! When you see a huge list containing numbers and words you don’t understand then you know you are not eating real food. The less ingredients that are listed on packaged foods, the better. This means that per gram weight of yoghurt, you get more of the good stuff such as calcium, vitamin B12, potassium and probiotics, because there is less of the bad stuff to dilute it. If you have a food processor, try blending some natural yoghurt with your choice of frozen berries. You will be left with a product that mimics frozen yoghurt but contains no added sugar (or other nasty chemicals for that matter). You’ll also be getting a lot more real fruit this way as ‘fruit-flavoured’ items tend to contain very little. Natural yoghurt has a smooth, creamy texture and not only is it a healthier and cheaper alternative to frozen yoghurt, but it can also act as a great substitute for things like sour cream or dip bases.

Lasagna Sheets vs. Sliced Eggplant

| ✓ Sliced Eggplant | $7.50/kg | Lasagna Sheets | $7.70/kg |

The final tip for today is to switch lasagna sheets for sliced eggplant! Sliced eggplant is cost-equivalent to home-brand lasagna sheets and a significantly cheaper option to wholemeal or gluten-free varieties. Eggplant is a rich source of fibre and contains B-vitamins which are crucial for energy metabolism. This simple switch will not just improve the nutrient profile of your lasagna, but it will enhance the taste and texture too! Roasted eggplant absorbs flavours from the other ingredients, intensifying the dish and resulting in a “melt in your mouth” texture (yum!). If you are suspicious about how this might turn out then the best thing you can do is to just try it for yourself. You may like to follow this super easy recipe from “Add A Pinch” as a guide: http://addapinch.com/easy-eggplant-lasagna-recipe/.

You should now be enlightened to that fact that so many of these overpriced products we think of as being “healthy” are actually falsely advertised as so, and to our benefit, there are much healthier and cheaper options available! If you require further assistance on how you can make healthier swaps at the supermarket that may just save you some cash, consult a dietitian for personalised advice.

References

1) Albert CM et al. Nut consumption and decreased risk of sudden cardiac death in the Physician’s Health Study. Arch Intern Med 2002;162(12):1382-7.

2) Ellsworth JL et al. Frequent nut intake and risk of death from coronary heart disease and all causes in postmenopausal women: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Nutrition Metabolism and Cardiovascular Disease 2001;11(6):372-7.

3) Hu FB et al. Frequent nut consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women: prospective cohort study. British Medical Journal 1998;317(7169):1341-5.

4) Fraser GE et al. A possible protective effect of nut consumption on risk of coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med 1991; 152: 1416-24.

5) Blomhoff R. et al. Health benefits of nuts: potential role of antioxidants. Brit J Nutr 2007;96(SupplS2):S52-S60.

6) Jenkins DJ et al. Almonds decrease postprandial glycemia, insulinemia and oxidative damage in healthy individuals. J Nutr. 2006;136(12):2987-92.

7) Parham M et al. Effects of pistachio nut supplementation on blood glucose in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomised crossover trial. Rev Diabet Stud. 2014 Summer;11(2):190-6.

8) Kendall CW et al. The glycemic effect of nut-enriched meals in healthy and diabetic subjects. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2011 Jun;21 Suppl 1:S34-9.

9) Wu T. Diabetes Mellitus in a nutshell. University of Sydney. RPA Hospital Diabetes Centre 2016.

10) AUSNUT 2011–13 Food Nutrient Database [Internet]. Food Standards Australia New Zealand. 2014 [cited 2016 Apr 06].

11) Eades M. A spoonful of sugar [Internet]. The Blog of Michael R. Eades, M.D. 2005 [cited 2016 Dec 20].

12) Greenfield B. Secrets of the Superhuman Food Pyramid: Benefits of Coconut Meat [Internet]. Superhuman Coach 2013 [cited 2016 Dec 20].

*** Product costs and information retrieved from Coles online on 19 December 2016

The original article can be found on: Ellipse Health – https://www.ellipsehealth.com.au/single-post/2016/12/21/Healthy-Eating-Doesnt-Have-to-be-Expensive

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Nutrition

Whether it affects you or someone close to you, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a challenging medical condition that requires ongoing management. The good news is that lifestyle factors, in particular nutrition, hold the potential to positively influence health outcomes and empower those with PCOS. It’s time to change the way we look at disease and come to be invigorated by the choices we make each and every day. This can all start with what we put into our mouths!

What is it?

PCOS is one of the most common medical conditions in young women. In fact, 1 in every 8 women of childbearing age is affected and unfortunately, many cases remain undiagnosed. In a nutshell, PCOS involves an imbalance of one or both of the following hormones:

– Testosterone (the male sex hormone) is higher than it should be

– Insulin (the hormone that helps to store energy after we eat carbohydrates) is higher than it should be.

What are the symptoms?

Women may experience some (not necessarily all) of the following symptoms:

– Lack of or irregular periods

– Struggling to fall pregnant

– Loss of hair from the head

– Excess growth of body hair

– Acne

– Deterioration of mental health

– Difficulty in losing weight

Insulin Resistance

At least two-thirds of women with PCOS also have insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia and metabolic dysfunction. These characteristics are very similar to those experienced in Type-2 Diabetes and so the mechanisms to treat and manage the two conditions often overlap. But what exactly is insulin resistance and what can be done about it?

Consider this scenario. You are the manager of a small business that employs five staff members. Your workers are given set workloads and their daily performance is outstanding. You decide to give your workers greater workloads because you want to get the most out of them, as any good business manager would. Your workers accept the challenge and continue to work as quickly and efficiently as they can. However, work begins piling up on their desks and the workers are starting to tire. You now must make the following business decision: Do you (a) employ new workers to keep on top of this greater workload? Or, do you (b) dial it back and inform your clients that deadlines will have to be extended?

You’d pick (a) right? I mean who wouldn’t take the opportunity to grow their small business and employ more staff if the work is flowing in? But what if this small business is your body? The workers are your insulin and the workload is glucose (blood sugar). Picking option (a) would mean that you need a larger office to accommodate the larger number of workers. Would you choose to increase the size of your body just so you can accept a greater workload? No! If this small business is your body and the workload is incoming glucose, you would most certainly pick (b) – you’d dial that workload right back and restore the efficiency of the workers you already have.

In PCOS, your body IS this small business and your insulin is less able to do its job of removing glucose from the blood. If the amount of glucose coming into your body is not being controlled, then you will produce more insulin in attempt to overcome this inefficiency. High concentrations of insulin are thought to stimulate androgen production (e.g. testosterone) and exacerbate many of the associated features and side-effects of PCOS. Insulin is also a storage hormone, and having excess amounts floating around means that excess energy from the food we eat will be stored as fat. Over time, this can lead to unwanted weight gain and an increased risk of developing diabetes and/or heart disease. Therefore, it is of great importance that women with PCOS control the amount of glucose going in to their bodies and improve their insulin sensitivity.

The Good News?

Whilst PCOS can be very challenging to manage and may require medical intervention, it’s important not to underestimate the huge role that lifestyle modifications such as diet and exercise play in managing the condition long term. Here are three of the most important nutritional tips to help you better control your blood glucose levels, improve your sensitivity to insulin and manage your PCOS.

#1 Reduce your sugar intake. In light of what we have discussed, it is important that you be mindful how much sugar is coming in through your diet to minimise the workload of insulin. Whilst not perfect, the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that adults reduce their added sugar intake to less than 6 teaspoons a day (~25 grams) for optimal health outcomes. To put this into perspective, 1 tablespoon of tomato sauce can have around 1 teaspoon (4 grams) of added sugars, and a single soft drink can have around 10 teaspoons (40 grams)! It must also be recognised that ALL forms of dietary carbohydrate are metabolised into glucose in your bloodstream. So whether it is carbohydrate from pure white table sugar or carbohydrate from wholegrain bread, your body is going to have to deal with the incoming glucose. In respect, reducing your sugar intake involves being mindful of the amount of total carbohydrate you are consuming each day in order to avoid unnecessary spikes in blood glucose and keep insulin levels low. Carbohydrate sources that have a minimal to low impact on blood sugar include foods like green leafy and cruciferous vegetables (spinach, kale, cauliflower, green beans, Brussels sprouts), pumpkin, fresh berries, nuts, seeds and natural yoghurt.

#2 Choose whole foods that are minimally processed, such as fresh fruit and vegetables, nuts and seeds, fish, milk, cheese, yoghurt and lean meats. When purchasing packaged foods, flip over to the Nutrition Information Panel and choose products that have less than 5g sugar per 100g. It’s also a good idea to check the Ingredients List to see if sugar has been added to the product. A lot of the times it will be, even when you don’t expect it! Aiming for 5 serves of vegetables and 2 serves of fruit everyday is a great challenge to help you displace processed, packaged food and surge you closer toward meeting your nutritional requirements. Another great tip is to fill at least HALF your plate with non-starchy vegetables at dinner time.

# 3 Do not fear fats! This may be the most important point of all because it has been engrained into our minds that fats are the devil however fats are an essential component of our diets and adding high quality fat to your meals actually slow the release of glucose from carbohydrates into your bloodstream – a major priority in PCOS! When choosing fats, go for those that are closest to their natural state, steering clear of cheap vegetable oils and packaged foods that have been overly processed and contain unstable fatty acids that can cause damage in your body. When purchasing fats and oils, check the label and avoid products that have been “refined” or “hydrogenated” as this tends to mean that trans fats are present. Natural, stable fats can be sourced from foods such as avocados, oily fish (mackerel, salmon, tuna), grass-fed meats, farm fresh eggs, nuts, seeds, nut butters, nut oils, olive oil, organic butter.

Last but not least… Exercise!

Exercise is key to a healthy lifestyle and PCOS management as it can improve your muscles’ sensitivity to the hormone insulin. Increasing your total muscle mass will mean that your body has an increased capacity to clear glucose from the blood. Australian adults are recommended to do physical activity for roughly 20-40 minutes every day, depending on intensity. Remember – physical activity is not just running on a treadmill or pumping weights at the gym, but can include a variety of activities like dancing, swimming, walking your dog and carrying your heaving shopping bags around too (there’s another excuse to go shopping if you needed one)!

So now you should be sitting up a little taller and feeling a little more positive about what you can do when it comes to PCOS lifestyle management.

The strategies provided are a broad guide to get you started, and we strongly recommend that you see one of our Accredited Practicing Dietitians (APD) and Accredited Exercise Physiologists (AEP) if you are seeking more tailored, individual advice.

This article was written by Metro Dietetics intern Jessica Turton (https://www.ellipsehealth.com.au/single-post/2016/12/14/Polycystic-Ovary-Syndrome-PCOS-and-Nutrition), and co-authored by Melissa Meier. The original version can be found at The Biting Truth.

Top 5 Misconceptions about Weight Loss

When it comes to weight loss, there are so many misconceptions surrounding it.

Today, we tackle our top 5 misconceptions about weight loss.

Misconception 1 – “Losing weight is as simple as ‘calorie in’ versus ‘calorie out’ (CICO)”

This is possibly one of the most common misconceptions around, giving rise to virtually every single weight loss product or program these days. The belief is that as long as we keep our caloric input less than our caloric output, we should lose weight.

There are a couple of fundamental flaws to that belief, which ultimately renders this calorie in versus calorie out (CICO) equation useless when it comes to weight loss.

To begin with, calories is an energy measurement, where 1 Calorie (often abbreviated to kCal) is the amount of energy needed to increase the temperature of 1L of water by 1 degree Celsius.

When we talk about calories in, we are referring to the amount of energy we are getting via the foods and beverages we consume. This part of the energy equation we can somewhat control.

However, when we talk about calories out, often the general public (and even some health and fitness professionals) will think about what our bodies expend through exercise or exertion. That is how the whole phenomena began with people assuming that if they did X number of hours on the treadmill, they could consume Y number of calories through food, and still technically be in “energy deficit”. One minor issue – exercise is not the only determinant of energy output.

Quite apart from the fact that our bodies use energy differently one person to another during exercise, there are other factors not taken into consideration when assuming calories out. Other things that contribute to our caloric output include:

Our BMR (Basal Metabolic Rate) – this is the amount of energy our bodies use to keep us alive. It is the energy our body uses to breathe, and to regulate our body temperature, and so forth. Unfortunately, our BMRs are so different person to person, and can also change dramatically depending on our body composition, food intake and other things such as illnesses.

TEF (Thermic Effect of Food) – We will touch on this more in Point 2, but essentially our bodies digest foods differently, depending on the amount of protein versus carbohydrates versus fats.

Our body also recognises when our intake drops too low below our current BMR, and responds by lowering our BMR. This is the body’s own mechanism to protect itself from literally withering away into nothingness. With a reduced BMR, your same food intake and exercise will no longer yield the same results with weight loss.

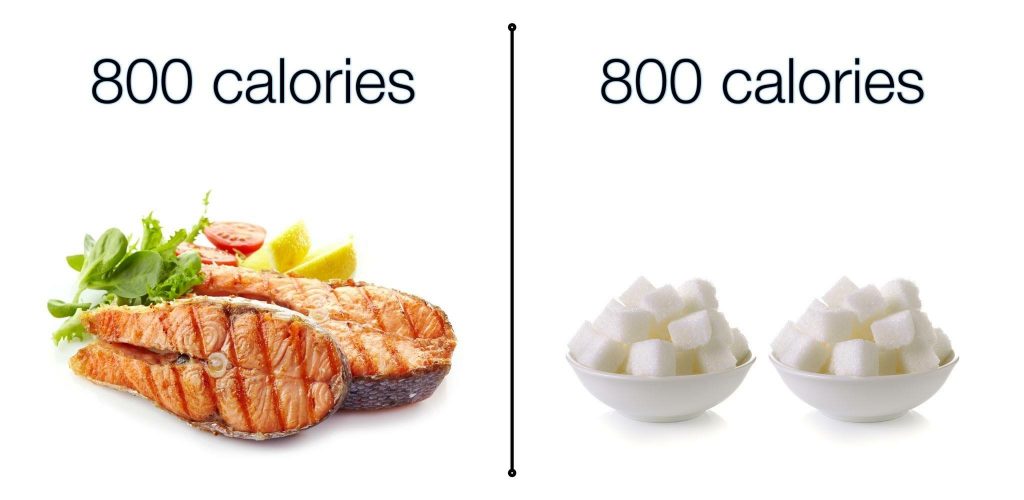

Misconception 2 – “A calorie is a calorie”

Knowing that losing weight by simply assuming CICO is futile, let’s now explore how counting calories is just as futile.

When we embark on counting calories, the automatic assumption is that a calorie is a calorie, no matter what is giving us that calorie. Quite apart from the fact that food is SO much more than just a caloric value, when you factor in the TEF you will realise that alas, a calorie is NOT a calorie. Let me explain.

Different nutrients affect digestion and metabolism differently.

For example, protein has the highest thermic effect of all the macronutrients (proteins, carbohydrates and fats), meaning that our body burns more energy when we eat protein rich foods. Protein also increases satiety (fullness), and suppresses our hunger via hormonal responses mediated by the hypothalamus, also known as the “control centre” of our brain.

Fats, whilst has the lowest thermic effect of the 3 macronutrients, has the slowest transit rate through our digestive tract. What this means is that fats can slow down the rate that food passes through us, and helps keep us feeling fuller for longer.

Therefore, a meal rich in proteins and fats will be much more satiating and keep us feeling satiated for far longer (at the same time burning more “calories”) than a meal rich in carbohydrates but void of proteins or fats. (see image below).

Knowingly, when we eat a meal that is more satiating, we then tend to eat: a) less of it, and b) less frequently. Ultimately, long term, this has a much greater impact on weight loss (or fat loss) than simply caloric restriction.

Misconception 3 – “Eating more frequently can speed my metabolism up”

How many times have you heard, or been told, that eating frequent small meals helps with boosting your metabolism?

Well, that’s not correct.

Metabolism is determined by total energy intake and requirements, but can be, in the short term, affected by factors such as exercise and stimulants (e.g. caffeine).

However, if your BMR is 1800kCal and your current daily intake is 1200kCal – you could eat that across 2 meals a day or 8 meals a day – it will make no difference to the fact that you are eating below BMR, and your metabolism will likely slow down still.

On the flip side, if your BMR is 1800kCal and your current daily intake is 1800kCal – you could again eat that across 2 meals a day or 8 meals a day, but your metabolic rate will unlikely drop off because you are meeting basic energy requirements to keep your metabolism up. In fact, if you are quite active, you will often need more than just your BMR to keep your metabolic rate high, and by eating to support your physical activity demands too, you would boost it even higher!

Misconception 4 – “Not eating breakfast will make me gain weight”

Somehow it has become a socially accepted “fact” that not eating breakfast will somehow make us gain weight (or at the very least will hinder our weight loss goals).

This belief is a follow through from the misconception that “skipping meals” or reducing meal frequency will result in a slowed metabolism. As pointed out above, this is not the case.

There is nothing special about breakfast, except the fact that it is a meal to help provide energy and set us up for the morning, for those who need it. Some people actually wake up and not feel like eating anything, and I think it is so important to point out that if this is you, there is absolutely NOTHING wrong with you, and you do not need to now force feed yourself in the hope that this will boost your metabolism and help you along with your health and weight loss goals.

In fact, fasting is a well-researched and well-documented approach for health and weight – I will be discussing this more in a blog later this month. Make sure you keep an eye out for it!

Disclaimer: Fasting does NOT equal starving – remember what we said earlier about not eating below your BMR? Eating below your BMR = starving. As long as you eat in line with your goals and you meet your BMR, not having 3 meals a day is still absolutely OK!

Misconception 5 – “My friend lost 30kg on a diet – I am going to do what my friend did because her results are amazing!”

Now that we know that it isn’t as simple as CICO, and that a calorie is NOT a calorie, we cannot expect that a diet that someone else did and had worked wonders will yield the same outcome for ourselves.

However, the way that most weight loss products and programs are marketed attract people to their products/programs by attempting to convince you that because “Anna” lost 30kg doing their program or using their shake, so can you!

Similarly, when we see our friends achieve massive weight loss doing what they are doing, we automatically try to copy it because we assume that it will work the same for us.

Please note that this is not the case (as explained throughout this article). There are so many nuances we need to consider (but simply don’t!):

> Age

> Gender

> Ethnicity

> Body composition

> Exercise types and intensities

> Goals

> Genetics

> Metabolic health and hormones

So, instead of trying to copy someone else’s weight loss success by doing what they did, why not seek some professional assistance in working out what works for YOU so you can eat and exercise in a way that not only suits your lifestyle but also your food preferences and physical health status and goals!

5 Things You Should Know About Your Weight

Today marks the start of Metro Dietetics’ ‘Weight Awareness Month’ – a perfect time to write a piece about weight. I’m hoping this will inform you about the perception and misconceptions about weight, and why losing/gaining ‘weight’ could be the wrong measure to focus your attention on.

- The numbers on the scales don’t tell you enough

Don’t focus all your energy and attention on the number of kilograms you weigh and set goals purely around your weight. Weighing yourself is not the most useful way to measure the type of body you have and the amount of ‘fat’ you want to lose.

You can easily fluctuate day to day depending on the time you weigh yourself, whether you have gone to the toilet and emptied your bowels, how much water and food you’ve had that day, and so forth.

You may find that you weigh the same, but look and feel very different (see point 3).

- BMI’s are misleading (don’t use it to determine your ‘healthy’ weight…ever!)

I’m sure you’ve all heard of the illusive term ‘BMI.’ BMI (Body Mass Index) is a measurement used to classify weight, being: underweight, healthy weight, overweight and obese. This is calculated by taking your weight and dividing it by your height to the power of 2 (kg/m2). BMI measurements can be useful when looking at population level data, but for an individual, this measurement is a lot less valuable and actually quite misleading. It does not take into consideration: gender, age, ethnicity and mostly importantly, body composition.

The most obvious example of a misleading BMI would be a body builder – clearly very fit and muscular individuals. I typed in ‘body builder profile’ on Google, and found that a professional body builder (Jay Cutler) weighed 118kg during contest and was 1.77m tall. This gives him a BMI of 38kg/m2 and classed him as ‘obese.’ Imagine how high the BMI would have been if Jay was actually shorter!

- Your focus should be shifted towards lean body mass

For the same volume, lean body mass (or muscle mass) weighs a lot more than fat does. Another way to put it is: for the same weight, muscle mass is denser and occupies a smaller volume compared to fat mass.

What does this mean for those who are fixated on scale-weight loss? It means that you can be doing all the right things, increasing physical activity and eating healthier, but the number on the scales may not change. Please don’t be disheartened! It could very well be that your body composition is changing and you’re becoming leaner. Losing fat and gaining muscle does not show on the scales!

Take me as a case study: I have weighed approx. 59-61kg for the last 8 years or so. I play soccer 3 times a week during the year and have periods of travelling and significantly reduced physical activity levels during the off season. My eating habits have never changed drastically. My weight has only every fluctuated by 1-2kg, despite looking quite different in the mirror and feeling very different / not fitting into my clothes. The difference in these 2 photos is about 2kg. In the photo on the right, it’s clear that I have a lot more fat deposited around my gut, hips and thighs (or maybe it’s just a bad angle??). The fact is, even though I had only gained a little on the scales, my body composition had changed greatly to have less muscle and more fat – which makes me appear ‘fatter’ and a lot bigger in terms of clothing size.

Getting your skinfolds assessed by an ISAK Accredited Anthropometrist or having a DEXA scan is an accurate way to measure your body composition and to find out your ‘body fat percentage.’

- Considering your body shape and where your deposit most of your fat is important

Research now suggests that individuals who store their fat around their belly are more likely to experience poorer health. As abdominal fat increases, so too does fat stored around your organs, causing inflammation and therefore having consequences on long-term health conditions such as type 2 diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia. Measuring the size of your waist and aiming to reduce this could be a better goal for you and a better indication of improving health, than to focus purely on overall weight.

- Weight should not be your only measurement of health

Obsessing over the number on the scales is not good for anyone! Whilst scale weight certainly can be used as an indicator for progress when weight loss is required, it should only be used as that – an indicator.

Other things you can focus on instead could be:

Decreasing your risk of long-term diseases

> Improving the quality of your diet

> Improving your fitness level

> Changing your body composition

> Improving mood and energy level

> Getting better quality sleep

> Fitting into your clothes better

> Losing centimeters around your waistline